ARTÍCULOS ORIGINALES

Consumption of Psychoactive Substances in

Educational Institutions: an Inquiry into the State of

Affairs in the Schools of Córdoba.

Lucchese MSM, Burrone MS, Enders JE, Fernández AR.

Revista Facultad de Ciencias Medicas 2014; 71(1):36-42

Admission Department, School

of Medical Sciences - Universidad Nacional de

Córdoba.Córdoba. Argentina. Enrique Barros s/n- Ciudad

Universitaria. admision@fcm.unc.edu.ar

Introduction

The illegal consumption of psychoactive

substances is an important psychosocial phenomenon.

According to Luengo, Kulis, Marsiglia, Romero, Gómez-

Fraguela, Villar and Nieri, consumption of substances by

adolescents is a public health problem with personal and

social implications(1). Against this background,

educational institutions constitute a place that fosters the

development of their higher psychological functions by

providing them with symbolic resources to build their

perception of the social world and of themselves as

individuals(2,3). EchavaríaGrajales states that

the school constitutes the scene where the manners of

thinking, feeling and inhabiting the world are shaped, and

where a universe of cultures and identities is framed. For

adolescents, schools are an important part of the changes in

the process of development of their autonomy. The

socialization processes that adolescents establish at school

may include drug consumption; school attendance is important

as a protection factor in contexts of vulnerability(4).

It is important to determine the relationship between

substance consumption, school environment and the school

standing of the students. As a result of these

considerations, the following questions arise: is it true

that state night-shift coeducational schools, with low

academic demands and lax discipline, foster drug

consumption? Is it true that adolescents with behavior

problems and low attendance rates are potential consumers of

illegal substances? Is it true that schools with high

academic and disciplinary standards, with clearly stated

behavior norms, do not facilitate the consumption of

psychoactive substances?

Objectives

Materials and Methods

Two approaches were used to carry out this

study. The quantitative approach was used for the first

stage, using the data gathered by the Second National Survey

of Secondary School Students carried out in Córdoba city in

2005. For the second stage, a qualitative approach was used.

The quantitative approach involved a correlational and

observational analysis. The work was performed on the data

recorded by the Second National Survey of Secondary School

Students, using a multistage probabilistic sample drawn from

a universe consisting of the entire population of students

of the schools included in the Córdoba Province School

Census of 2004. The sample was representative of students of

the Córdoba Province aged 13, 15 and 17 years, comprising

4593 students in all. The questionnaire employed was the one

designed and validated by SEDRONAR for secondary school

students, consisting of 97 closed questions, and this study

focused on 13 questions, grouped according to: school,

school standing of the student, and psychoactive substances

consumption by students.

To assess the school characteristics, the

following aspects were taken into account: type of school

(state, private, and other), shift (morning, afternoon, and

night), level of academic demand (high, fairly high,

somewhat high, and low). As regards student school standing:

sex (male, female), age (13, 15 and 17 years), grade (8th,

10th, and 12th), number of grade

repetitions (none, one, two, or more), existence of behavior

problems (often, sometimes, and never), and frequent absence

from school (yes, no). As regards psychoactive substances

consumption: whether the student did or did not consume

psychoactive substances. The analysis comprised summary

measurements and multivariate and factorial multiple

correspondence analysis. Statistical processing of data was

carried out as bivariate analysis, through categorical data

(chi-squared test, Mantel Haenzel or Fisher’s test), in

order to determine the risk ratio and confidence intervals (CIs)

for each variable under study. In all cases a significance

level of p < 0.05 was established.

The second stage consisted of an ethnographic

study. The schools (both state and privately managed

state-supervised, “private” for short henceforward) were

chosen by an intentional, cumulative and sequential sampling

method until a point of data saturation was reached. This

stage began once the results of the quantitative had been

obtained. Ten in-depth interviews were carried out, with

school principals, deputy principals, regents, and members

of the schools technical staffs. The questions were adapted

to the various situations of the educational institutions as

regards consumption, school, and school standing of the

students. The qualitative data thus gathered was analyzed

using the Glaser and Strauss’ comparative constant method.

Validation was done by means of inter-method triangulation(5).

Results

The National Survey in Córdoba comprised 4593

students. The mean age of students in the sample was 14.91 ±

0.03, with a range going from 11 to 22 years. 42.85% of

students were male and 57.15%, female. When comparing the

mean age of the groups stratified by sex, it was detected

that male mean age was higher than female mean age, namely

14.96 ± 0.04 vs 14.87 ± 0.03 respectively (p < 0.01). As for

the type of school, it was found that 54.45% of students

attended state schools, the remaining being at privately

managed schools, and that 73.74% of the total student

population was in the morning shift.

For the relationships between school shift,

sex, school academic demand, and school discipline demand,

the results were as follows.

As regards the relationship between

consumption and school shift, the morning shift shows less

consumption than the afternoon and night shifts (62%, 72%,

88.33%, respectively; p < 0,001). Moreover, a difference was

observed in the consumption of both legal and illegal

substances according to school shifts, with adolescents in

the morning shift consuming less than those in the afternoon

and night shifts (p < 0,001). As regards monthly prevalence

of some illegal drug, it was detected that for schools with

a fairly high level of academic demand and discipline (p =

0.0187) students do no consume illegal drugs. Besides, it

was detected that female students consume less than male

students (p = 0.0273). It was also detected that night-shift

schools with low academic and disciplinary demands present a

higher consumption risk. As regards levels of academic

demand, the study shows that adolescent consumption

increases as these levels decrease (p < 0.02). This study

has detected that age is an important variable associated

with consumption (p = 0.0053). Consumption was observed to

increase with age.

|

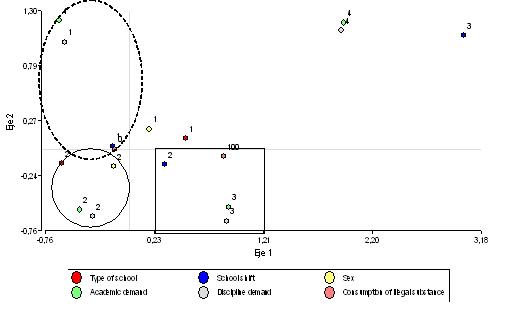

Figure 1:

Multivariate analysis of life prevalence of

consumption of na illegal substance, school shift, academic

demand, discipline demand and sex of student.

Ref: consumption of illegal substance: 0 NO;

100 YES

Sex: 1: male; 2, female

Type of school: 1: state; 2: private

School shift: 1: morning; 2: afternoon; 3:

night

Academic demand: 1: high; 2: fairly high; 3:

somewhat high; 4: low

Discipline demand: 1: high; 2: fairly high;

3: somewhat high; 4: low

Figure 1 shows in the first quadrant the

grouping of state school, male sex, low academic demand, low

discipline demand, and night school shift. The second

quadrant (broken-line ellipse) shows the grouping of high

academic demand, high discipline demand, morning shift and

no consumption of illegal substances. The third quadrant

(continuous line ellipse) shows the grouping of private

school, female sex, and fairly high academic and

disciplinary demand. The last quadrant (rectangle) groups

consumption of some illicit substance, afternoon shift and

low academic and disciplinary demand.

Figure 2, which corresponds to the analysis

of the relationship between type of school (private or

state), school standing of adolescents and drug consumption.

The first quadrant (continuous line ellipse) demonstrates

the grouping of males with frequent behavior problems in

school and consumption of alcoholic beverages and some

illegal substance. The second quadrant (broken-line

ellipse) associates private schools and no repetition, with

high attendance rates and no consumption of illegal

substances. The third quadrant (continuous line rectangle)

shows the association of female sex, no consumption of

alcoholic beverages, and no behavior problems, whereas the

fourth quadrant (broken line rectangle) shows the

relationship among frequent school absenteeism and

repetition of one grade during the course of studies.

Figure 2:

Multivariate analysis of type of school

(private or state), adolescent school standing and

consumption of drugs. (n=4593). Year 2005.

Ref: Sex: 1: male; 2, female

Type of School: 1: state; 2: private

Repetition: 1, none; 2: two; 3, two or more

Behavior problems: 1, often; 2, sometimes; 3,

never

Frequent absence: 1, yes; 2, no

Illegal substance: 0: consumption; 100: no

consumption

Prevalence of alcoholic beverages: 0:

consumption; 100: no consumption

As regards qualitative analysis of substance

consumption by adolescents, through inquiries about what and

when they consume, the following statements were gathered:

“Teenagers get drunk; they pay a price in

order to become part of a group. Boys and girls alike drink

alcohol”

(Interview Nº 1)

“There is consumption, more in teenagers

attending the afternoon shift than in those in the morning

shift. There are some punctual cases, and the remaining ones

consume marijuana. As regards alcohol, it is usual

particularly on weekends, alcohol is accepted as something

natural and so is marijuana”

(Interview Nº 2)

“Marijuana consumption has arrived in school.

There are cases of students who steal pills from their

parents or grandparents”

(Interview Nº 2)

“50% of students smoke cigarettes, between

60% and 70% consume alcohol and 3 or 4 students consume

illegal substances, particularly since 2008”

(Interview Nº 4)

“There is consumption of and dealing in drugs

in the school”

(Interview Nº 8)

“They consume alcohol and arrive in school

already drunk”

(Interview Nº 2)

Alcohol is mainly consumed on weekends; this

consumption is considered as something completely natural,

and it is done to follow the fashion, to imitate the group

peers and for the sake of fun. In two state schools, one

student was reported to have entered the school in a drunken

state, and another one was found in the act of consuming an

illegal substance.

As regards level of academic demand,

interviewees had the perception that it is variable. Some

private institutions perceive themselves as demanding, and

the effects of this demand can be seen in the rate of

admission of their students to university. Some state

schools identify their level of academic demand as normal,

whereas another one declares it to be high; it was also

observed that the demand may depend on the teachers and the

subjects they teach. Moreover, coeducational morning-shift

schools were detected to have higher academic demands than

those of the afternoon and night-shifts, which is related to

consumption of substances, and coincides with the

quantitative results of this study.

As regards levels of disciplinary demands,

the following statements were identified:

“Lack of discipline does not affect the

majority of students”

(Interview Nº 1).

“Public policies tend to do all that is

necessary to retain students; for instance, if they are

absent for a total of 45 days, nothing is done (…)”

(Interview Nº 2).

“We could say that discipline has not

worsened since 2003/2004, but that it varies according to

the teacher”

(Interview Nº 3).

“An orderly class facilitates the development

of activities. As for discipline, we are very demanding and

fortunately, as a result of the work of monitors, order can

be maintained without coercion”

(Interview Nº 4).

“Monitors are in charge of both

administrative and pedagogical tasks”

(Interview Nº 5).

“Students enter the classroom and leave it at

their will; my class starts at 8:00, but some of them arrive

at 8:40… they just say “I’m coming back in a moment, I’m

going to have breakfast”. “They enter the classroom with pop

music at a very high volume”

(Interview Nº 10).

“There is no discipline demands … there is a

monitoring notebook, but nothing is actually done”

(Interview Nº 9).

These statements of interviewees permit to

detect that discipline has changed as compared to previous

years. Private schools evince a strict discipline which

purports to control the class and to apply penalties in case

of faults; the code of social conduct is recognizable in the

development of daily school activities. State schools

exhibit extremes cases as regards discipline and order,

ranging from the recognition of the value of discipline and

order to a complete laxity. Some schools refer the violation

of norms to their code of social conduct.

Private schools tend to have a more uniform

approach to disciplinary matters, whereas state schools

evince more variation in the application of norms, which may

result, according to the situation, in protection factors or

risk factors. The variety of norms established by different

educational institutions implies different behaviors of the

institutions as such. Some institutions analyze discipline

problems, others tend to expel students, and others

privilege retention of students following ministerial

policies. Flexibility in the matter of interpretation of

norms may be seen in some state schools, but is not found in

private schools.

As regards repetition rates, it ranges

between 5% and 25% in the majority of schools. Only one

school had a repetition rate of 60% from the first to the

third year. Repetition rates are higher in state schools

than in private schools. Re-enrolment as a result of

absenteeism occurs in both types of schools, though in state

schools some cases of three instances of re-enrolment were

recorded for a student in a year. Repetition rates and

re-enrolment are governed by provincial and institutional

policies, and evince different approaches in state and

private institutions. The flexible application of norms is

the result of contingent problems rather than of academic

long-term policies; this may eventually lead to dropping out

of some students because they cannot account for the

educational training they have received. Some educational

policy decisions are not related to levels of academic and

disciplinary demand, as they should be as a result of the

state responsibility and the heterogeneity of the

educational system.

Discussion

With reference to type of school and

attendance shift, this study concluded that adolescents

attending morning-shift schools evince less consumption of

illegal substances than those attending afternoon or night

shifts, a finding that coincides with those of the study

carried out by the ObservatorioHondureño(6). As

regards levels of academic demand, this study concludes that

consumption by students increases as academic demand

decreases, which agrees with the first comparative study on

the use of drugs by the school population in Latin American

countries(7). This also coincides with the

results of the work by AnnelieseDörr and her team, who found

that consumers have a perception of the school as less

demanding than those who do not consume, and that schools

with more lax discipline Foster consumption(8).

Similarly, an article by García del Castillo states that

consumption increases when students perceive the school as

less demanding in matters of discipline(9). These

results are reinforced by a study carried out by CICAD,

which stated that in most Latin American countries the

prevalence of consumption year of any illegal substance

doubles when the school is perceived by students as lax in

disciplinary demands(7).

As regards school standing of adolescents and

its association with consumption of psychoactive substances,

it is observed that frequent absenteeism, behavior problems

and repetition are linked to the consumption of psychoactive

substances. Similarly, a study by VázquezValls and his team

detected a clear relationship between drug consumption and

low academic performance, high absenteeism, dropping out of

school, and low educational expectations(10).

Oliveira and his team detected that the use of psychoactive

substances interferes with lessons and school activities

(11). Another comparative study in Latin America

found that students who get low marks and/or have repeated

some school grade exhibit higher drug consumption rates than

those having a better academic performance(2).

The results of the CICAD study in Latin America indicate

that students who have repeated courses in school show

higher rates of drug consumption in all countries(12,7).

On the other hand, the study by VázquezValls and his team

asserts that adolescents with good marks and high

involvement with their school show a higher self-esteem and

consume less alcohol(13).

CasoNiebla y

HérnandezGuzmán have noted, in a study on a model to explain

low school performance in Mexican adolescents, that

self-esteem has a direct effect on the consumption of

substances, which in turn is related to poor school

performance(14).

Conclusion

It is observed that the differences in the

consumption of legal and illegal substances between the

students surveyed, in relation to the school shift, point to

less consumption in adolescents attending the morning shifts

as compared to those in the afternoon and night shifts.

Repetition and behavior problems were associated to

consumption of some illegal drugs by adolescents, whereas

those schools that are adequately organized towards their

educational goals, and having high levels of academic demand

and clarity of disciplinary norms, become institutions whose

adolescent students do not consume psychoactive substances.

Bibliography

1.

López Larrosa S, Rodríguez-Arias Palomo L. Factores de

riesgo y de protección en el consumo de drogas en

adolescentes y diferencias según edad y sexo. Psicothema.

2010; 22 (4): 568-573.

Full Text

2. Estudios Nacionales sobre

uso de drogas en población escolar secundaria de Argentina,

Bolivia, Brasil, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, Paraguay, Perú y

Uruguay. las ONUDD, CICAD/OEA, SEDRONAR, CONACE, CONALTID,

CONSEP, DEVIDA y JND.2006.

3. Rivas Flores J. La

perspectiva cultural de la organización escolar. Marco

institucional y comportamiento individual.Educar.2003;

31:109-119.

Full Text

4. Echavarría Grajales C. La

escuela un escenario de formación y socialización para la

identidad moral. Revista Latinoamérica de Ciencias Sociales,

Niñez y Juventud. 2003; 1(2).

Full Text

5. Paul J. Between Method

Triangulation.

The International Journal of

Organizational Analysis.1996; 4(2): 135-153.

6. Estudio Nacional en Honduras

(2005-2006) Consejo Nacional contra el narcotráfico.

Observatorio Hondureño sobre Drogas. Magnitud del Consumo de

Drogas en Jóvenes Estudiantes Hondureños. 2006.

7. CICAD-OEA. Jóvenes y drogas

en países sudamericano: Un desafío para la política pública.

Primer Estudio comparativo sobre uso de drogas en población

escolar secundaria de Argentina, Bolivia, Brasil, Colombia,

Chile, Ecuador, Perú y Uruguay. Primer Ed. Lima: Tetis Graf

E.I.R.L; 2006.

Full Text

8. Dörr A, Gorostegui ME, Viani

S, Dörr B. Adolescentes consumidores de marihuana:

implicaciones para la familia y la escuela. Salud Mental.

2009; 32: 269-278.

Full text

9. García del Castillo J.

Género, Drogas y Futuro. Salud y Drogas. 2005; 5(002):7-10.

Full Text

10. Vázquez Valls R, Ramos

Herrera M, Barajas M. Consumo de droga(s) y aprovechamiento

escolar la convivencia y sus problemas; microculturas

juveniles en la escuela. X Congreso Nacional de

Investigación Educativa. 2010.

Full Text

11. Oliveira M, Ribera L,

Villar M. Factores de riesgo para el consumo de alcohol en

escolares de 10 a 18 años, de establecimientos educativos

fiscales en la ciudad de La Paz.

Bolivia (2003-2004). Rev.

Latino-Am. Enfermagem [Revista em Internet]. 2005

[citado05deJunio2009]; 13(spe):

Full Text

12. CICAD-OEA. Estudio de

consumo de sustancias psicoactivas en las Américas.

Washington; 2006.

13. Villarreal González M,

Sánchez Sosa J, Musito Ochoa G.The role of family

communication and school adjustment in adolescent´s violent

behavior.

En Frías Armenta M y Corral

Verdugo V, eds. Bio-Psycho-social perpectiveson

interpersonal violence. 2010:143-165.

14. Caso Niebla J, Hernández

Guzmán L Variables que inciden en el rendimiento académico

de adolescentes Mexicanos.

Revista Latinoamericana de

Psicología. 2007; 39(3).

|