ARTICULO DE REVISIÓN

Disease Mongering in Neurological

Disorders

Silvia Kochen1-2 ; Marta Córdoba2

Revista Facultad de Ciencias Medicas 2013; 70(4):217-222

1-2 Centro de Neurociencias

Clínicas y Aplicadas. Epilepsia, Cognición y Conducta.

Sección de Epilepsia, Div Neurología, Hosp “R.Mejía” – Inst.

de Biología Celular y Neurociencias, Fac. Medicina, Univ.

Buenos Aires –Consejo Nacional de Investigación Científico y

Tecnológico (CONICET)

2 Div. Neurología. Hospital R. Mejía , Buenos Aires,

Argentina.

Correspondence should be

addressed to Silvia Kochen,

skochen@retina.ar

If out of curiosity, the readers take a few seconds to

search on the Internet the expression “diseases mongering”,

they will see that "to promote or sell disease" is an

enforced definition. They will also find out that the term

competes in popularity with many frequently used words, even

with popular actors or sportsmen. Besides it will appear a

number of “new diseases" or novel groupings or categories of

“old diseases”. The main and common characteristic of all

these "diseases" is that they are amenable to be treated

with drugs. The first reason seems to be the advances in

scientific knowledge. However, we should incorporate other

considerations such as the interest of the pharmaceutical

industry in selling their products.

Almost 20 years ago, Lynn Payer1 used the term “disease

mongering” for the first time as the strategy of the

pharmaceutical industry to expand the boundaries of

treatable illness in order to increase the market (Table 1)

2. This concept was recently defined as “the selling of

sickness that widens the boundaries of illness and grows the

markets for those who sell and deliver treatments.”3

Therefore, the pharmaceutical industry redefines what is

normal and what is pathological modifying the concept of

disease. Much disease mongering relies on considering normal

biological or social variation as pathologies. It also is

based on the portrayal of disease risk factors as if it was

a pathological state in itself. The vicious circle is

completed when pharmaceuticals are used to treat risk

factors because“ anyone who takes medicines is by definition

a patient”4-6).

Disease mongering exploits the deepest atavistic fears of

suffering and death. In neurology added aspects are related

to cognitive function, or illness that cause great

disability, high mortality, or are surrounded by stigma.

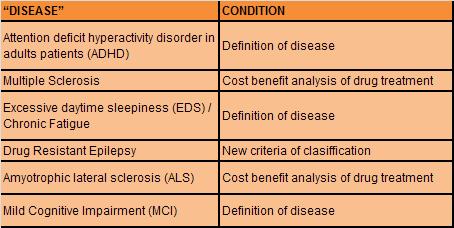

The principal aim of this paper is generate awareness in

neurologists about of relatively new situation. We selected

some “new diseases” or disease mongering aspects in “old

disease” (Table 2). Although this corpus is just a sample,

it is useful to remark the effect of disease mongering in

neurology field. The choice was based on lack or weak

evidence in one or more condition: a- definition of disease;

or b- cost benefit analysis of drug treatment; or c- the use

of new classification that assign criteria of severity in a

disease. In every case, this situation implies the use of

expensive treatments. We describe a brief review of each of

the entities included.

|

|

There is an important advertising campaign aimed at

potential consumers in order to “improve cognitive functions”

in mentally and neurologically healthy people, this

statement is very complexe and ambiguous. However, there is

a very large offer of drugs. The prescription of modafinil,

adrafinil, methylphenidate, inderal, piracetam, aniracetam,

amphetamines has increased in the last time7

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults

patients (ADHD)

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE,

2011) highlights the weak evidence in the definition of this

"disease": “this would be best conducted as an

epidemiological survey to answer the ADHD in adults”. In

1986, Nasrallah et al.8 reported brain atrophy in adult

males treated with amphetamines during childhood concluding:

“since all of the HK/MBD [hyperkinetic/ minimal brain

dysfunction] patients had been treated with psychostimulants,

cortical atrophy may be a long-term adverse effect of this

treatment”. In spite of this research other authors

published “Recent investigations with magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) provide converging evidence that a refined

phenotype of ADHD is characterized by reduced size of the

frontal lobes and basal ganglia “9. However there had

been no such studies of ADHD-untreated cohorts10.

Although ADHD is a recognized pathology (ICD, DSM-IV) in

children, we can not stop thinking that the possibility of a

drug treatment can shoot some diagnostics, which does not

happen with disorders no treatable with drugs such as

dyslexia. ADHD is a symptom, a syndrome or a disease

diagnosed in 7.8% of U.S. children between 4-17 years (4.4

million children), according to results of a parent survey

conducted in 2003, of which 56% were medicated at the time.

Also in Spain the consumption of methylphenidate fivefold

from 1992 to 2001 with an estimated increase in annual

consumption of 8%. Could be possible to reduce diagnoses

understanding ADHD from a model of mental functioning rather

than from a model based on observable behavior and the sum

of symptoms, sometimes collected through global

questionnaires.5,11 In recent studies, in children and in

adults, observed increased in the prevalence of this

diagnosis with a trend of increasing prescribing of ADHD

drug treatment, however no demonstrate more evidence

diagnostic.12-14

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and Chronic Fatigue

Both categories EDS and Chronic Fatigue, can be

considered together taking into account that there is

overlaping on the definition used to define each of them,

even their existence as diseases or syndromes is contested

15. Nevertheless, there is abundant mass media advertising

refered to the “good results” achieved with psychostimulants.

A recently editorial of Neurology16, describe in relation

a paper published in the same journal17, as despite

having a Class I level of evidence in the treatment protocol

with modafinil in EDS and chronic fatigue, detailed analysis

showed did not improve fatigue symptoms, nor were there any

benefits in the psychomotor vigilance test18.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

Despite there are clinical guides that contemplate mild

cognitive impairment as a defined disease19, their

consideration as a clinical entity according to some authors

is still a matter of debate. In this context of uncertainty,

clinical trials have been developed in the attempt to study

the effects of ChEIs (donepezil, rivastigmine, and

galantamine) in delaying the conversion from MCI to

Alzheimer disease or dementia.20 Although the use of

ChEIs in MCI was not associated thus far, with any delay in

the onset of AD or dementia, the safety profile showed that

the risks associated with ChEIs were not negligible21.

However appears information in scientific journals and in

mass media that encourages the use of these drugs to "prevent"

these dreaded diseases.

The disorders that mainly leads to a deterioration of motor

skill as multiple sclerosis or fatal disorder such as

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, high influence for patients,

healthcare systems, and society as a whole:

Multiple Sclerosis

It is remarkable the profound analysis made by James

Raftery.22 What happened with multiple sclerosis risk

sharing scheme in United Kingdom represent a unique

situation where the NHS is paying for thousands of patients

to receive drugs that monitoring data suggest are not

effective. This scheme was set up in 2002 after the National

Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)

recommended against the use of interferon beta and

glatiramer acetate. It is based on outcome analysis, not

only in cost benefit analysis. There was an agreement that

prices would be reduced if patient outcomes were worse than

predicted. Disease progression was not only worse than

predicted by the model used by NICE23, but even worse

than the untreated control group. In the same way, Cochrane

multiple sclerosis group has proposed that the efficacy of

interferon on exacerbations and disease progression in

patients with relapsing remitting MS was modest after one

and two years of treatment. Interferon administered by the

oral route was not effective for prevention of relapses.

Longer follow-up and more uniform reporting of clinical and

MRI outcomes among these trials might have allowed for a

more convincing conclusion.24,25 Recently in a

systematic review indicating that the anti-inflammatory

effect of Interferon β is unable to prevent MS progression

once it has become established.26 Nevertheless, there was

not any price reduction, moreover, in our country the prices

are more than double that in developed countries27.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

Several ALS therapies have shown promising results in

preclinical models of motor neuron disease. However, most of

them failed in human studies. A remarkable progress in

understanding the cellular mechanisms of motor neuron

degeneration has not been matched with the development of

therapeutic strategies to prevent disease progression or to

extend survival longer clinical trials.28

The current estimations of the cost-effectiveness of

riluzole must be analized cautiously. The uncertainty of the

benefits in the economic analysis is due to the

overconsideration of the survival gain that is experienced

in a determined disease stage. The quality of life utility

weights upon ALS health states and the gained life

expectancy for individuals who take riluzole. Estimates from

different trials suggest a gain in median tracheostomy free

survival time of 2 months to 4 months.29-31 This

treatment implies an increase in costs for the health

service. In addition to the unsatisfactory results, the

great impact of these costs in developing countries is

almost impossible to afford.

Drug resistant epilepsy

Epilepsy is one of the most prevalent neurological

disorders, that can be effectively prevented and treated at

an affordable cost for most of patients. Different

epidemiological studies estimated that up to 22.5% of

patients with epilepsy have drug-resistant epilepsy. In this

group the use of new drugs, more expensive, or nondrug

therapy such as epilepsy surgery should be considered.32

A new definition recently proposed for ILAE (International

League Against Epilepsy)33 includes in this category

patients that present seizures, opposed to patient seizure-

free, without special consideration, i.e. seizures without

consciousness, or only during sleep, or one seizure by year.

Although before to mentioned definition, there was no

unified definition of drug resistant epilepsy, those

patients who had affected their quality of life were

included as drug resistant or refractory epilepsy. Numerous

of patients now included in this group, were not consider in

this category previous to recent definition.34 It is

evident that in this new classification the concept quality

adjusted life year (cost/QALY) is not considered, and allows

that many more patients are liable to receive more expensive

and sophisticated treatments.

Conclusion

Pharmaceutical companies are not the only actors in this

field. Physicians, patients, mass media, politicians, also

play a role with different contributions, but together

multiply the effect of disease mongering. There must be

awareness of all stakeholders to know this problem at the

moment of making decisions related with diagnosis and

prescription.

It is necessary the implementation issues in latinoamerica

as the “Sunshine Act”, part of the Affordable Care Act,

created in USA, requires manufacturers to submit a list of

physicians and teaching hospitals who received from them a

transfer of value, but neither was implemented even in the

country of origin.

We consider it is essential that health professionals become

aware of this relatively new condition, which increases more

and more, probably have even more serious impact on

developing countries for their limited resources and

inequitable health condition.

References

1- Payer, Lynn “Disease-Mongers: How Doctors, Drug

Companies, and Insurers are Making You Feel Sick” Wiley,

USA, 1994.

2- Andresik D., " Disease Mongering: El arte de fabricar

enfermedades”, Biophronesis, Revista de Bioética y

Socioantropologia en Medicina, 2009, nº.2, v.4"

3- Jairaj Kumar C., Abhizith D., Ashwini K., Arunachalam K.,

Hegde B. M., “Awareness and Attitudes about Disease

Mongering among Medical and Pharmaceutical Students”, April

2006 , Volume 3 , Issue 4 ,e210, PLoS Medicine, published by

the US Public Library of Science (PLoS).

Full Text

4- Rose G (1985) Sick individuals and sick populations. Int

J Epidemiol 14: 32–38.

Full Text

5- Moynihan R. Cassels A. Selling sickness, Vancouver:

Greystone Books, 2005. ISBN 1553651316

6- Cuestas E. The new strategies for disease mongering; Rev

Fac Cien Med Univ Nac Cordoba. 2011;68(3):89-93.

Full Text

7- Gilbert D, Walley T, New B. Lifestyle medicines. BMJ.

2000; 321:1341

Full Text

8- Nasrallah HA, Loney J, Olson SC, McCalley-Whitters M,

Kramer J, et al. (1986) Cortical atrophy in young adults

with a history of hyperactivity in childhood. Psychiatry Res

17: 241–246

PubMed

9- Swanson J, Castellanos FX (1998) Biological bases of

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Program and

Abstracts, NIH Consensus Development Conference on Attention

Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; 16–18 November 1998;

Bethesda, Maryland. pp. 37–42.

10- Baughman FA (1999) ADHD—Total, 100% fraud [video].

Produced from the official video of the NIH Consensus

Development Conference on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity

Disorder; 16–18 November 1998; Bethesda, Maryland.

11- Sixto ME., Martínez González C., Quintana Gómez JL.,

“Disease mongering, el lucrativo negocio de la promoción de

enfermedades”. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2009;11:491-512

Scielo

12- Doshi JA, Hodgkins P, Kahle J, Sikirica V, Cangelosi MJ,

Setyawan J, Erder MH, Neumann PJ. Economic impact of

childhood and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

in the United States. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2012 Oct;51(10):990-1002.

PubMed

13- Barry CL, Martin A, Busch SH. ADHD medication use

following FDA risk warnings. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2012

Sep;15(3):119-25.

PubMed

14- Batstra L, Frances A. DSM-5 further inflates attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012

Jun;200(6):486-8.

PubMed

15- Holgate ST, Komaroff AL, Mangan D, Wessely S. Chronic

fatigue syndrome: understanding a complex illness. Nat Rev

Neurosci. 2011 Jul 27;12(9):539-44.

Abstract

16- Richard M. Dasheiff, Editorial Neurology, Modafinil is

not the new caffeine Richard M. Dasheiff. Neurology

2010;75:1764–1765

Full Text

17- Kaiser PR, Valko PO, Werth E, et al. Modafinil

ameliorates excessive daytime sleepiness after traumatic

brain injury. Neurology 2010;75:1780 –1785.

PubMed

18- Kesselheim AS, Myers JA, Solomon DH, Winkelmayer WC,

Levin R, Avorn J. The prevalence and cost of unapproved uses

of top-selling orphan drugs. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31894ç

Full Text

19- The NICE guideline on supporting people with dementia

and their carers in health and social care this clinical

guideline has been amended to incorporate the updated nice

technology appraisal of drugs for alzheimer’s disease,

published in march 2011 (http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta217 ).

20- Gauthier S., Touchon J., “Mild cognitive impairment is

not a clinical entity and should not be treated”. Arch

Neurol 62: 1164–1166. 2005

Abstract

21- Raschetti R., Albanese E., Vanacore N., Maggini M.,

“Cholinesterase inhibitors in mild cognitive impairment: A

systematic review of randomised trials”. PLoS Med 4(11):

e338. doi:10.1371/journal. pmed.0040338. 2007

Full Text

22- Raftery James. Multiple Sclerosis risk sharing scheme: a

costly failure. BMJ 2010; 340:c1672

Full Text

23- NICE. Multiple Sclerosis-beta interferon and glatiramer

acetate. Technology appraisal 32.2002

Full

24- G Rice, B Incorvaia, L Munari, G Ebers, et al.

Interferon in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis.

Editorial Group: Cochrane Multiple Sclerosis Group.

Published Online: 21 JAN 2009, The Cochrane Collaboration.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

25- Noyes K, Bajorska A, Chappel A, Schwid SR, Mehta LR,

Weinstock-Guttman B, Holloway RG, Dick AW.

Cost-effectiveness of disease-modifying therapy for multiple

sclerosis: a population-based study. Neurology. 2011 Jul

26;77(4):355-63.

PubMed

26- La Mantia L, Vacchi L, Rovaris M, Di Pietrantonj C,

Ebers G, Fredrikson S, Filippini G.J Interferon β for

secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: a systematic

review. Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012 Sep 5. [Epub ahead

of print]

27- De Robles P., Recchia L., Gonorasky S. , Gonzalez

Aguilar P. El costo derivado del número necesario a tratar.

Revista Neurológica Argentina 2006; 31: 59-64

28- A Pratt, E Getzoff, J Perry, Amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis: update and new developments. Degener Neurol

Neuromuscul Dis. 2012 February; 2012(2): 1–14.

PubMed

29- Ludolph A. and Jesse S. “Evidence-based drug treatment

in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and upcoming clinical

trials” Ther Adv Neurol Disord (2009) 2(5) 319–326

Full Text

30-

Guidance on the Use of Riluzole (Rilutek) for the

Treatment of Motor Neurone Disease Published by the National

Institute for Clinical Excellence January 2001

31- Miller RG, Mitchell JD, Moore DH. Riluzole for

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)/motor neuron disease

(MND) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012

PubMed

32- Shorvon SD. Epilepsia. 1996;37 Suppl 2:S1-S3. Review.

33- Kwan P., Arzimanoglou A., Berg A., Brodie M., Hauser W.,

Mathern G., Moshé S., Perucca E. , Wiebe S., French J.;

“Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: Consensus proposal

by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on

Therapeutic Strategies” ; Epilepsia Volume 51, Issue 6,

pages 1069–1077, June 2010

34- B Westover, J Cormier, M Bianchi, M Shafi, R Kilbride, A

Cole, S Cash. Revising the ‘‘Rule of Three ’’ for inferring

seizure freedom ; Epilepsia, 53(2):368–376, 2012

PubMed

|