|

TRABAJO ORIGINAL

Food preferences and their

“decision contexts” as predictors of dietary pattern.

Preferencias

alimentarias y su contexto de decisión como predictores del

patrón alimentario.

María M Andreatta(1,2), María L del Campo(2), Adrián

Carbonetti(1), Alicia Navarro(2)

Revista Facultad de Ciencias

Medicas 2011; 68(1): 14-19

( ) Centro de

Investigaciones y Estudios sobre Cultura y Sociedad - Unidad

Ejecutora, CONICET. Gral. Paz 154, 2º piso, Córdoba Capital.

(2) Escuela de Nutrición, Facultad de Ciencias Médicas,

Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Pabellón de las Escuelas,

E. Barros s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, Córdoba Capital.

E-mail:

alicianavarro74@yahoo.com.ar ;

maryandreatta@hotmail.com

Introduction

A growing number of epidemiological studies on diet and

its association with nutritional status or the risk for

developing certain pathologies, such as the non-communicable

diseases – such as cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular

diseases - have been carried out and published in the last

decades

(1). These studies have mainly focused on food

consumption and nutrient intake and their relationship with

metabolic aspects

(2), being food frequency questionnaire –

FFQ – the usual method for estimating dietary intake in

epidemiological studies because it provides a valid and

reliable estimate of the usual food intake in a variety of

populations

(3, 4).

Although studies on nutrient and food intake have

contributed to the understanding of the development of

several highly prevalent diseases, it does not show why,

where or how people choose certain foods and reject others

(5). It has been suggested that previous experiences and

knowledge about nutritition, health status, availability and

access to food, culture, position in the social scale,

gender, and the influence of the mass media all of them have

an impact on most of the daily food choices

(2, 6-8). In addition, the specificity of the relationship between

society and nature at every historical period also affects

food choices

(9). All these issues belong to what we have

called the “food decision context”.

It is worthy to bear in mind that people eat meals, and not

just isolated foods. These meals or preparations are usually

the result of a combination of foods, according to precise

rules. Moreover, even certain single-food cooking

preparations follow rules

(10). The way food is turned into

meals using specific procedures and technologies, also

involves people’s conceptions about diet, health, gender and

their belonging to society ranks

(10, 11).

Summing up, the complex human dietary behaviour cannot be

understood by simply using food frequency methods alone. It

is also necessary to elucidate why some foods are chosen and

others are rejected, and why foods are combined in certain

manners

(12). Consequently, food preference and its decision

context approach may explain more accurately these issues.

Thus, the FPQ is a quick and easy approach to assess usual

diet

(13). In the present study, we decided to design and

validate a FPQ to be applied in adult subjects for

nutritional epidemiological studies.

Materials and Methods

Food preference questionnaire design

Unidimensionality, simplicity, speed, responsiveness and

understandability were the criteria considered in designing

this FPQ

(14, 15). An informed consent form was also

elaborated

(16).

A pilot study was performed with three

adults of both sexes before applying the FPQ with the sample.

Subjects and data collection

The fieldwork was carried out between February and April of

2010 in Córdoba, a Mediterranean city of 1.300.000

inhabitants located in Argentina.

The FPQ was applied to 60 adult subjects of both sexes,

living in Córdoba and nearby cities of the Greater Córdoba

region, taking as a reference a previous study of FFQ

validation carried out by our group

(4). People with

digestive tract diseases or with long-term modifications of

their diet were excluded. The subjects were contacted in a

private clinic and a public hospital of Córdoba city and

interviewed after signing the informed consent. It is

important to note that the sample was obtained from a

hospital population, since this FPQ will be used in future

studies devoted to search the relationship between food

preferences and non-communicable diseases, and patients will

be contacted at the same location where the FPQ was applied.

Subjects were requested to point out their food preferences,

ingredients and method of preparation, culinary learning

resources, sources of recipes, purchasing strategies of each

food preparation and cultural roots of the decision to

consume that food. They were also requested to specify the

frequency of consumption of each preparation, information

that was used as an indicator of dietary patterns, and

permitted further validation of the FPQ

(17). Other

epidemiological information collected at the interview

included sex, weight and height, age, educational attainment,

employment status, health insurance, housing conditions,

income, and perception of food in relation to the health-disease

process. All these data are relevant in order to understand

the context of the food decision.

The study was conducted following all the international

ethical norms for research in human populations

(16) and was

approved by the Ethics Review Board of Health Research of

the Ministry of Health of the Province of Córdoba.

Statistical analysis

The validity of the FPQ was estimated through the

correlation between the number of subjects who indicated a

preference for a particular preparation and the frequency of

its consumption. As previously explained the frequency of

consumption is the reference method for estimating dietary

intake

(14, 17).

The Spearman correlation coefficient (rs) was calculated by

using SPSS 17.0. The coefficient of determination (r2) was

also computed in order to estimate the percentage of data

variability explained by the association between the two

variables (18, 19).

Results

Relevant characteristics of interviewed subjects

A descriptive analysis showed that 62% (n = 37) of the

individuals were men and 38% (n = 23), women, being the

average age 55.6±16 years old. Three social strata were

defined by considering the employment status and educational

attainment

(20). Data showed that 50% (n =32) of the people

belonged to the lowest stratum, 25% (n=16) to the middle

stratum, and the other 25 % (n=16) to the highest stratum,

respectively.

Food preferences and frequency of consumption

Over 194 favourite meals or foods were mentioned during the

interviews. In order to allow statistical processing, these

food preferences – FP – were regrouped into ten categories

according to their main ingredients and methods of

preparation. These groups are listed below:

- FP 1: Roasted, baked, grilled or fried red meats or

sausages served with or without vegetables and/or cereals.

- FP 2: Roasted, baked, grilled or fried poultry served with

or without vegetables and/or cereals.

- FP 3: Mixed preparations cooked by moist heat, such as:

stew, rice with chicken, paella, soup, pickles, and sauces.

- FP 4: Preparations of cereals, cereal products or potatoes,

with vegetables and/or meat, such as: pasta, pizza, polenta,

pies, steak sandwiches, potato cake, and potato chips.

- FP 5: Milk, yogurt, ice cream and flan.

- FP 6: Vegetables, salads, chop suey.

- FP 7: Fruits.

- FP 8: Bakery: criollos (variety of typical bread with a

high content of salt and animal or/and vegetable fat), white

bread and crackers served with or without jam, cheese and/or

butter.

- FP 9: Cheese.

- FP 10: Seafood; roasted or grilled fish served with or

without vegetables or cereals; sushi.

The average monthly frequency of consumption (MFC) was

calculated for each group.

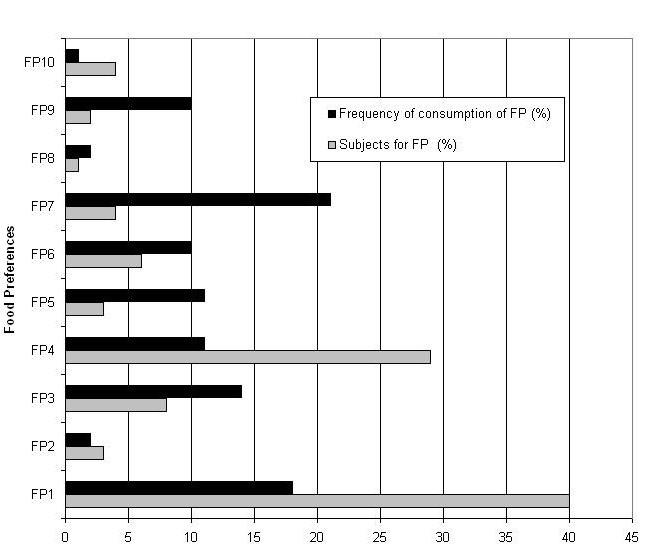

As shown in Figure 1, most people preferred the red meat

group (n=77) and the group with preparations of cereals,

cereal products or potatoes (n=56). In addition, the most

frequently consumed foods were those of the fruit group (MFC=440),

the red meat group (MFC=372), and mixed preparations cooked

by moist heat (MFC=285). The greatest overlaps between FP

and the frequency of consumption were observed in the food

chosen by poultry group (FP2 n=5 and MFC=45) and the bakery

group (FP8 n=3 and MFC=30).

|

|

Fig. 1:

Food preferences and their frequency of consumption.

Córdoba, 2010 |

.

FPQ validity to estimate dietary pattern

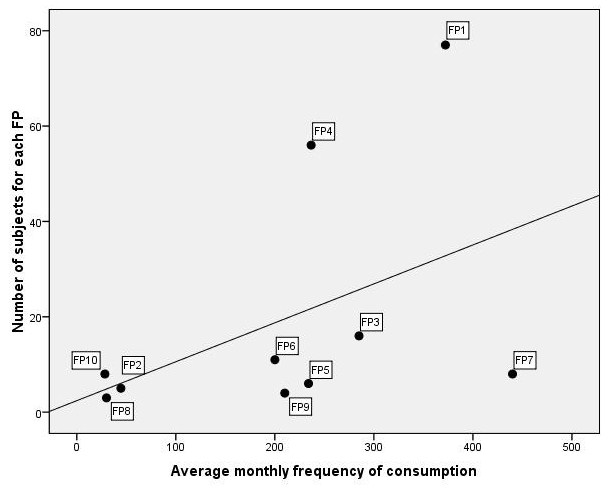

The correlation between the number of subjects who indicated

a preference for a particular preparation, and its frequency

of consumption gave a result of rs=0.5 (p <0.1). This value

indicates a moderate correlation between the two variables.

Figure 2 shows the linear trend of correlation. Thus, the

dietary patterns of adult population from Córdoba could be

estimated by assessing food preferences.

|

|

Fig. 2:

Correlation between food preferences and frequency

of consumption. Córdoba, 2010. |

The determination coefficient had a value of r2= 0.25. This

indicates that 25% of the dietary pattern of these subjects

was explained by their preferences, whereas the biological,

psychological and socio-cultural components of the food

decision context, in additon to their complex relations, may

also contribute in a certain degree to understand better the

choice of food intake.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop a quick and easy

questionnaire to assess the usual diet of adults through

their food preferences. We found that the dietary patterns

and usual food intake could be estimated by assessing the

food preferences of the studied population, given that the

Spearman correlation was rs = 0.5 for a confidence level of

90%.

Food preferences (FP) have been used for decades by

marketing departments in the food industry to satisfy the

consumption and tastes of people, whereas the quali-quantitative

frequency of food consumption (FF) has been the preferred

approach to assess the usual intake in epidemiological

studies on non-communicable diseases

(3, 4, 21-24). Although

both strategies are closely related, it is generally

considered that the FP method only provides a rough

approximation to the actual food consumption. Nevertheless,

recent research has found significant correlations between

both methods. Drewnowski and Hann

(25) investigated the

association between FP and food consumption in college women

and found a correlation of 0.4 between the two variables.

Another similar study conducted with college students of

both sexes in Mexico, gave a correlation of 0.48

(13). Also,

a current and more complex investigation revealed that

dietary patterns related to cardiovascular risk in adult

males could be efficiently estimated through FP

(26).

Using the coefficient of determination, we have shown that

the influence of the so-called “food decision context" is

very important in the construction of FP and dietary

patterns. In fact, it has been previously demonstrated that

adult FP are strongly influenced by age, sex, health status,

educational level and income

(27-29). Similarly, the local

or regional food culture, position in the social scale and

the mass media are significantly involved in everyday food

choices

(2, 6-8). Economic access to food also determines

and interacts with the other aspects of the food decision

context. Regarding this latter factor, in the present study

we observed that although most subjects preferred meals from

the group of red meat, fruits were the most frequently

consumed, as expected

(30,31). Due to red meats are

expensive, they cannot be consumed as frequently as desired

(10). On the other hand, the general belief that fruits are

"healthier" than red meats is gaining acceptance. Therefore,

we can speculate that fruits are consumed more often because

they are considered “good for health”, despite them not

being chosen as favorite foods

(32). Similarly, meals

prepared with vegetables and dairy products were frequently

consumed but only had a moderate preference.

Besides, the preference and the frequency of consumption of

preparations based on cereals and cereal products or

potatoes with meat and/or vegetables, such as pasta, pizza,

pies, and steak sandwiches, among others - and mixed

preparations cooked by moist heat, such as stew, rice with

chicken, and soup, among others - followed the same trend of

preferences. Both these types of meals are very popular

(30), forming part of Argentinean food culture and also are

cheaper, which could explain why they are among the favorite

foods with a high frequency of consumption

(10).

Food preferences have the capability of introducing the

affective or attitudinal component of the usual diet,

compared with the method of frequency which is based on the

recallinf of past intake of the surveyed subjects

(25). These two methodologies not only correlate significantly,

but also complement each other since they effectively

evaluate different aspects of the same phenomenon: the diet

of human groups related to a particular place and time.

In conclusion, the FPQ is a valid instrument for a quick and

easy estimate of consumption and dietary patterns in adults.

It also has the advantage of not relying on the recalling of

the past regular diet, as in the case of the FFQ. Moreover,

the inclusion of the food decision context is a valuable

approach to examine the socio-cultural and individual

processes that influence the food preferences of individuals,

thus on the health preservation and avoidance of the risk of

related diseases.

|

ACKNOLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by SeCyT-UNC

and CONICET.

The authors are indebted to Professors Oscar

Pautasso (MD, PhD) and Susana Asia de Leoni (MD, PhD)

for facilitating the conduction of the surveys in

the Sanatorio del Salvador and the Hospital Nacional

de Clínicas, respectively.

We also acknowledge the help given by Eliana Álvarez

Di Fino and Sofía Alzuarena in applying the FPQ, as

well as to Aldo R. Eynard (MD, MS, PhD) and Ernesto

Grasso (MD) for their suggestions and careful

revision of the manuscript.

The authors are grateful to Paul David Hobson (PhD),

native speaker, for his technical assistance in the

English revision.

|

Reference

1. Byers T. The role of epidemiology in developing

nutritional recommendations: past, present and future. Am J

Clin Nutr; 1999, 69:1304s-08s.

Full text

2. Mela DJ. Food Choice and Intake: The Human Factor.

Proceedings of the Nutrition Society; 1999, 58:513–521.

PubMed

Full text

3. Willett WC, Sampson L. Dietary assessment methods.

Proceedings of the second international conference. Am J

Clin Nutr; 1995, 65:1097S–368S.

4. Navarro A, Osella AR, Guerra V, Muñoz SE, Lantieri MJ,

Eynard AR. Reproducibility and validity of a food-frequency

questionnaire in assessing dietary intakes and food habits

in epidemiological studies in Argentina. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res; 2001, 20: 365-370.

PubMed

5. Bellisle F. How and why should we study ingestive

behaviors in humans? Food Qual Pref; 2009, 20: 539-544.

6. De Garine I, Vargas LA. Introducción a las

investigaciones antropológicas sobre alimentación y

nutrición. Cuadernos de Nutrición; 1997, 20: 21-28.

PubMed

7. Logue AW. The psychology of eating and drinking, an

introduction. Freeman and Company. New York, USA, 1998. 2ª

ed.

8. Birch LL. Development of Food Preferences. Ann Rev Nutr;

1999, 19: 41–62.

PubMed

9. Hintze S. Apuntes para un abordaje multidisciplinario.

In: Álvarez M, Pinotti L V, comp. Procesos Socioculturales y

Alimentación. Editorial Del Sol México, 1997, p.15.

10. Aguirre P. Estrategias de Consumo: Que Comen los

Argentinos que Comen. Miño y Davila Editores. Buenos Aires,

2005.

11. Fischler C. El (h) omnívoro. El gusto, la cocina y el

cuerpo. Editorial Anagrama. Barcelona, 1995.

12. Contreras Hernández JJ, Gracia Arnaiz M. Alimentación y

Cultura. Perspectivas antropológicas. Editorial Ariel.

Barcelona, 2005.

13. Díaz Mejía MC. Preferencias Alimentarias como

Alternativa al Estudio de Patrón Dietético. Rev Esp Nutr

Comunitaria; 2002, 8: 29-34.

14. Polit DF, Hungler BP. Investigación Científica en

Ciencias de la Salud. Editorial Mc Graw-Hill Interamericana.

Filadelfia, 1995. 5ª ed.

15. Casas Anguita J, Repullo Labradora JR, Donado Campos J.

La encuesta como técnica de investigación. Elaboración de

cuestionarios y tratamiento estadístico de los datos (II).

Escuela Nacional de Sanidad. Madrid, 2002.

16. CIOMS/Council for International Organizations of Medical

Sciences. International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical

Research Involving Human Subjects. [on line] CIOMS.

Switzerland, 2002 [Consulted 14/10/2009] Available at:

http://www.cioms.ch/publications/guidelines/guidelines_nov_2002_blurb.htm

17. Willett WC. Nutritional Epidemiology. Monographs in

Epidemiology and Biostatistics. Vol. 15. Oxford University

Press. Oxford, 1990.

18. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing

agreement between two methods of clinical measurement.

Lancet; 1986, 1: 307-310.

PubMed

19. Conover WJ. Practical nonparametric statistics. John

Wiley & Sons. New York, 1998. 3rd. ed.

20. Vinocur P. Metodología de la Investigación Evaluativa.

In: Evaluación de un Programa de Alimentación Escolar: el

caso argentino. OPS/OMS. Buenos Aires, 1990, p. 2, 9-19.

21. Tuorila H, Cardello AV, Lesher LL. Antecedents and

consequences of expectations related to fat-free and

regular-fat foods. Appetite; 1994, 23:247–63.

Abstract

22. Gould J, Densk GA. Children’s preferences for product

attributes of ready-to-eat pre-sweetened cereals. J Food

Prod Mark; 1996, 3:19–38.

23. Hess MA. Taste: the neglected nutrition factor. J Am

Diet Assoc; 1997, 97:S205-S207.

PubMed

24. DeSarbro W, Young MR, Rangaswamy A. A parametric

multidimensional unfolding procedure for incomplete

nonmetric preference/choice set data in marketing research.

J Mark Res; 1997, 34: 499–516.

Abstract

25. Drewnowski A, Hann C. Food preferences and reported

frequencies of food consumption as predictors of current

diet in young women. Am J Clin Nutr; 1999, 70:28–36.

Full

text

26. Duffy VB, Lanier SA, Hutchins HL, Pescatello LS, Johnson

MK, Bartoshuk LM. Food preference questionnaire as a

screening tool for assessing dietary risk of cardiovascular

disease within health risk appraisals. J Am Diet Assoc;

2007, 107:237-45.

PubMed

27. Harnack L, Block G, Lane S. Influence of selected

environmental and personal factors on dietary behavior for

chronic disease prevention: a review of the literature. J

Nutr Educ; 1997, 29:306–12.

Abstract

28. Drewnowski A. Taste preferences and food intake. Annu

Rev Nutr; 1997, 17:237-53.

29. Drewnowski A, Henderson SA, Hann CS, Barratt-Fornell A.

Age and food preferences influence dietary intakes of breast

care patients. Health Psychology; 1999, 18: 570-578.

PubMed

30. Andreatta MM, Navarro A, Muñoz SE, Aballay L, Eynard AR.

Dietary patterns and food groups are linked to the risk of

urinary tract tumors in Argentina. Eur J Cancer Prev; 2010,

19: 478-484.

PubMed

31. Navarro A, Muñoz SE, Eynard AR. Diet, feeding habits and

risk of colorectal cancer in Córdoba, Argentina. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res;1995, 14: 287–91.

Abstract

32. Orlando MF, Andreatta MM, del Campo ML, Navarro A.

Representaciones Sociales de la Alimentación y el Proceso

Salud-Enfermedad en sujetos con cáncer en Córdoba,

Argentina. 2010 [manuscript under consideration].

|